Residents of Ashley Gardens

From its earliest days Ashley Gardens has been noted for the prominence of its residents, and this is still true today: when you live in Ashley Gardens you often see your neighbors' names on book jackets and hear their voices on BBC Radio 4. Residents include leading political figures, senior government officials, well-known musical and theatrical personalities, high-profile QCs and other professional people, chairmen of FTSE-100 companies, influential literary figures and journalists, high-ranking military officers, scientists and academics, and many more.

There are many stories about former residents of Ashley Gardens, and here are a few of them.

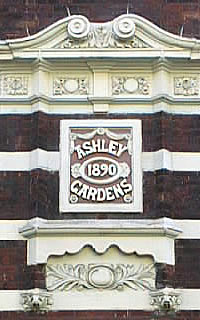

Ashley Gardens built beginning in 1890.

"The First Ten Years"

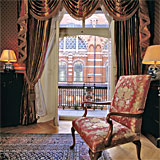

" ... offered a very different London lifestyle, central and convenient, generous in accommodation and advanced in design. Who would move in? Who would be able to tolerate the appalling noise and dirt associated with the construction of a Cathedral, a Roman Catholic cathedral at that and of enormous proportions, next door? Of course, for many these innovative developments offered a pleasant alternative for families living mainly in the country: husbands and fathers could reduce London expenses and entertaining in reasonable style: space was provided for domestic servants."

", as it was completed, rapidly established its social importance. Kelly's Directory for the 1890s indicates that tenants were happy to move in as the blocks were completed, some even being tempted from other new developments. Block 1 was virtually full by the end of 1890 with blocks 2 and 5 following in occupation by the end of 1891. ... All the blocks attracted pretty well the same social mix; MPs, army and navy officers, medical doctors and lawyers pursuing their careers were the neighbors of a large number clearly living on reasonable private means."

—"The World of the New: The First Ten Years", by Valerie Kingman. In Ashley Gardens: Backward Glances, London: Ashley Gardens Residents Association, 1990.

George Bernard Shaw: Ashley Gardens as "the New" (1893)

"Who were to be the 'New'? The 1890s were the decade of the New Drama and the New Woman. As Bernard Shaw said, 'we of course called everything advanced "the New" at that time.' , with the builders and decorators still at work, seemed extraordinarily well to represent 'the New'."

"Bernard Shaw wrote the 'topical comedy' The Philanderer in 1893. ... The first act is set in : Shaw's stage directions with their usual clarity create the atmosphere." [The spelling "Ashly Gardens" reflects Shaw's interest in simplified spelling, as does "Shakespear" further on.]

ACT I

A lady and gentleman are making love to one another in the drawing-room of

a flat in in the Victoria district of London. It is past

ten at night. The walls are hung with theatrical engravings and

photographs ... . The room

is not a perfect square, the right hand corner at the back being cut off

diagonally by the doorway, and the opposite corner rounded by a turret window

filled up with a stand of flowers surrounding a statue of Shakespear. The

fireplace is on the right, with an armchair near it. A small round table,

further forward on the same side, with a chair beside it, has a yellow-backed

French novel lying open on it. The piano, a grand, is on the left, open, with

the keyboard in full view at right angles to the wall. The piece of music on

the desk is "When other lips." Incandescent lights, well shaded, are on the

piano and mantelpiece. Near the piano is a sofa, on which the lady and gentleman

are seated affectionately side by side, in one another's arms.

... She is in evening dress. The gentleman ... is unconventionally but smartly dressed in a velvet jacket and cashmere trousers. His collar, dyed Wotan blue, is part of his shirt, and turns over a garnet coloured scarf of Indian silk, secured by a turquoise ring. He wears blue socks and leather sandals. The arrangement of his tawny hair, and of his moustaches and short beard, is apparently left to Nature; but he has taken care that Nature shall do him the fullest justice.

"That such a play should have been set in , so soon after the first tenants had moved in, indicates what the development represented—a new style which would appeal to the progressive mind."

—"The World of the New: The First Ten Years", by Valerie Kingman. In Ashley Gardens: Backward Glances, London: Ashley Gardens Residents Association, 1990.

Thomas Hardy at Ashley Gardens (1895)

"During the spring they [the Hardys] paid a visit of a few days to the Jeunes at Arlington Manor, where they also found Sir H. Drummond Wolff, home from Madrid, Lady Dorothy Nevill, Sir Henry Thompson, and other friends; and in May entered a flat at , Westminster, for the season. While here a portrait of Hardy was painted by Miss Winifred Thomson. A somewhat new feature in their doings this summer was going to teas on the terrace of the House of Commons -- in those days a newly fashionable form of entertainment. Hardy was not a bit of a politician, but he attended several of these, and of course met many Members there. On June 29 Hardy attended the laying of the foundation stone of the Westminster Cathedral, possibly because the site was close to the flat he occupied, for he had no leanings to Roman Catholicism. However, there he was, and deeply impressed by the scene."

—The Later Years of Thomas Hardy, 1892-1928 by Florence Emily Hardy (New York: Macmillan, 1930)

Anthony Powell is Born at Ashley Gardens (1905)

"I was born in London, 21 December, 1905, the winter solstice … ; the hour, towards one o’clock of a Thursday afternoon; the place, 44 Ashley Gardens, Westminster, a furnished flat rented for the occasion in one of the several redbrick blocks in that rather depressing area between Victoria Street and the Vauxhall Bridge Road. My father, Philip Lionel William Powell, lieutenant in a regiment of the Line, had been married to my mother for a year and a day. She was second of the three daughters of Edmund Lionel Wells-Dymoke, barrister-at-law. Both her parents were dead.

Expected to survive at most two days, I seemed about to follow them, so christening took place without delay in the flat. Later, a more formal ceremony was held over the way at St. Andrew’s, a Gilbert Scott church destroyed inthe blitz, its site now a car park."

—To Keep the Ball Rolling; The Memoirs of Anthony Powell by Anthony Powell (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001, orig. pub. 1983)

"The Greatest Change in the English House" (1910)

"Perhaps in one respect the greatest change which has been made in the English house is the adoption of "flats"; commenced ... in , Westminster, they have spread throughout London. In consequence of the great value of the sites on which they are sometimes built, to which must be added the cost of the houses pulled down to make way for them, the question of expense in material and rich decoration has not always been worth considering ... . The increasing demand for these, however, shows that they meet, so far as their accommodation and comfort are concerned, the wants and tastes of the upper and middle classes."

—R.P.S. [R. Phené Spiers, sometime Master of the Architectural School, Royal Academy, London], in Encyclopædia Brittanica, 11th ed. (Cambridge: University Press, 1910), s.v. "House"

Maugham describes Ashley Gardens (1919)

[Chapter 4] I was led up to Mrs. Strickland, and for ten minutes we talked together. I noticed nothing about her except that she had a pleasant voice. She had a flat in Westminster, overlooking the unfinished cathedral, and because we lived in the same neighbourhood we felt friendly disposed to one another. The Army and Navy Stores are a bond of union between all who dwell between the river and St. James's Park. Mrs. Strickland asked me for my address, and a few days later I received an invitation to luncheon.

My engagements were few, and I was glad to accept. When I arrived, a little late, because in my fear of being too early I had walked three times round the cathedral, I found the party already complete. Miss Waterford was there ... .

The dining-room was in the good taste of the period. It was very severe. There was a high dado of white wood and a green paper on which were etchings by Whistler in neat black frames. The green curtains with their peacock design, hung in straight lines, and the green carpet, in the pattern of which pale rabbits frolicked among leafy trees, suggested the influence of William Morris. There was blue delft on the chimneypiece. At that time there must have been five hundred dining-rooms in London decorated in exactly the same manner. It was chaste, artistic, and dull.

When we left I walked away with Miss Waterford, and the fine day and her new hat persuaded us to saunter through the Park. "That was a very nice party," I said.

[Chapter 58] ... while the pair conversed I took stock of the room in which we sat. Mrs. Strickland had moved with the times. Gone were the Morris papers and gone the severe cretonnes, gone were the Arundel prints that had adorned the walls of her drawingroom in ; the room blazed with fantastic colour, and I wondered if she knew that those varied hues, which fashion had imposed upon her, were due to the dreams of a poor painter in a South Sea island.

—W. Somerset Maugham, The Moon and Sixpence, (London: William Heinemann,1919)

D-Day is planned in Ashley Gardens (1943)

"... a brief and intriguing reference in the second volume of Dirk Bogarde's autobiography Snakes and Ladders [Chatto & Windus, 1978] when as a young and newly-qualified Air Photographic Interpreter he was involved in the early planning of D-Day 'in the high-ceilinged sitting room in a requisitioned mansion flat in , Victoria'. The date was late autumn 1943."

"He wrote to us in February" [1990]:

London, 4.2.90

... What a long time ago all that was. I have really forgotten so much. All I can do is offer a few broken fragments ... .

We began the planning of D.day in a stripped-out drawing room in one of the Mansion Flats in . I think it was on the second or third floor ... . We spent the nights on our camp beds in the empty bedrooms. Our batmen inhabited the basements ... or ground floors. We ate at a large restaurant opposite the fore court of Victoria Station. ...

Sorry not to be more helpful ... but I was pretty young then; it WAS a long time ago!

Dirk Bogarde

"... a letter from Brigadier Richard Vernon CBE which gives a vivid account of his time in —early March 1944 to mid May 1944. He writes ..."

I was responsible for the Operational Planning for the British Army side of 'OVERLORD'. ... There were a number of visitors to at that time. Certainly General Eisenhower came ... certainly Admiral Vian and Air Marshal Broadhurst were often there as the Senior Naval and Air Officers ... .

"... a letter written by Colonel S. K. Gelbert about Mulberry Harbour ... "

... preparations for the Mulberry Operation were integrated through the Port Operating Committee sitting in , opposite Westminster Cathedral. This was chaired by the Senior Naval Officer, at that time Captain Petrie RN. ...

[Some blocks of Ashley Gardens down near Francis Street were lightly damaged by enemy bombing during the war, but Block 2 survived unscathed.]

—"Wartime Years 1939–1945", by Margaret Fournier and Barbara Freeth. In Ashley Gardens: Backward Glances, London: Ashley Gardens Residents Association, 1990.

Harrods delivers to Ashley Gardens.

"Lord Jenkins of Ashley Gardens" (1959)

"This Law Lord conferred a minor honour on our homes by taking “” as a place name to distinguish his barony from those of other Jenkinses, as is the custom with fairly common surnames. ... David Llewellyn Jenkins was born in Devon in 1899 ... Charterhouse ... military service ... Balliol ... Lincoln's Inn ... Inland Revenue ... Court of Appeal ... became a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary in 1959."

"When asked to choose a place name for his title, he is reputed to have stated that he was just 'Lord Jenkins of 24 ', and proposed as the motto for his grant of arms, 'Up Jenkins!' Garter King of Arms of the day objected to such an undignified title and the flat number was duly dropped. So was the motto, which became instead 'Non sine jure'—not nearly so much fun."

—"Lord Jenkins of Ashley Gardens", by Lady Ann Gibson. In Ashley Gardens: Backward Glances, London: Ashley Gardens Residents Association, 1990.

The quotations above from the book Ashley Gardens: Backward Glances, (London: Ashley Gardens Residents Association, 1990) are included here by the kind permission of the Ashley Gardens Residents Association. A copy of this volume, published by the Ashley Gardens Residents Association to commemorate the centenary of the building of the first blocks of Ashley Gardens, is included with the flat.